At last night’s presidential debate, Vice President Kamala Harris told the American public she has “a plan” to alleviate America’s housing shortage, help small businesses, and “address the price of groceries.” That plan, like the rest of her policies, is elusive, but in a recently released “issues page” on her campaign site, she listed cracking down on “on anti-competitive practices” as a top priority. On the campaign trail she has promised that, if elected, she’ll call for “the first-ever federal ban on corporate price gouging on food and groceries” within her first hundred days in office.

With that line of attack, Harris has certainly tapped into a vein of voter anger: Lots of Americans are upset about their grocery bills, which rose dramatically during the inflation that followed the pandemic and have never come back down. Food prices increased by 11 percent in 2022, professor Ricky Volpe, of Cal Poly’s Agribusiness Department, told The Free Press. And while they’re only projected to rise 0.7 percent in 2025, those 2022 grocery prices have stuck. Americans still notice when they pay $5.24 for a pound of ground beef that cost only $3.80 a few years ago.

Unsurprisingly, a survey conducted by the Food Industry Association last month found that 69 percent of Americans feel their income hasn’t kept up with food inflation. That group includes significant percentages of older consumers (Boomers and Gen X) as well as people at the low end of the income scale.

But it’s worth asking: Why have food prices gone up so much? And does price gouging—the practice of jacking up prices during a natural disaster or other short-term emergency—really have anything to do with it? Volpe told me that, in fact, if food prices are rising beyond what consumers feel is reasonable, the food companies themselves play a surprisingly small role in the price hikes. Grocery stores, for instance—even giant superstores—are intensely competitive. Grocery store profit margins are among the lowest in all of American business, often as low as 1 percent.

According to Volpe, the rising costs of labor, shipping, and packaging have increased more than food prices since the onset of the pandemic and have played a more significant role. Matt Lind, 31, owns a food distribution company, Farmlind Produce, that purchases fresh fruits and vegetables from farms nationwide and trucks them to grocery stores and restaurants on the East Coast. “Post-Covid,” he told me, “freight out of California was around $6,000 this time of year. Last week, I paid as much as $8,400.”

In addition to freight, Lind’s fleet of 28 trucks has cost more to operate since the pandemic, when he was paying, on average, $2.60 per gallon of diesel. Now, he spends over four dollars per gallon. “Customers might think that the retailer and the wholesaler are taking advantage, but there’s so much overhead in this industry to keep it going,” he said.

To get a handle on whether Harris’s proposal would confront the source of rising prices—or is just pie in the sky—The Free Press looked at what’s behind prices in three staples of the American diet: eggs, beef, and salty snacks.

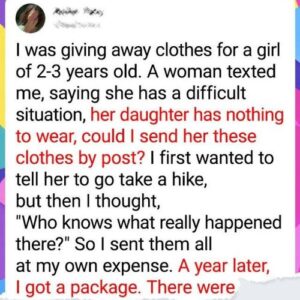

Eggs: When Hens Catch the Flu

In January 2023, the price of eggs hit an all-time high, $4.82 per dozen on average. The main reason? Millions of chickens were dying from avian influenza, or bird flu. Prices then decreased on average throughout the rest of 2023, hitting a low of $2.07 per dozen in September as the bird flu ran its course, but rose to $3.08 per dozen this July thanks to a second outbreak.

The CDC reported that as of August, more than 100 million poultry have been culled since 2022 as avian influenza continues to affect flocks nationwide.

This is a basic aspect of price changes in a capitalist economy: If supply (the number of egg-laying hens) goes down, the high demand for the remaining eggs can prompt price hikes.

Why isn’t that price gouging? That’s really a political question more than an economic one. If prices rise quickly, politicians like Harris are quick to blame greedy corporations, whereas economists view it as a natural—even healthy—part of an economy under stress, as we noted in The Free Press several weeks ago.

But consider this as well: If a chicken farm loses thousands of poultry due to bird flu, it still has overhead to cover, wages to parcel out, and shipping costs to pay. None of these costs go down just because a lot of chickens are dead. Does the avian flu qualify as the kind of unexpected emergency that a politician would call “price gouging?” Or is it just part of the food production cycle, like bad weather? Most economists would say it’s the latter.

Brian Moscogiuri, vice president of U.S. egg supplier Eggs Unlimited (Slogan: “Any Egg. Anywhere”), said in an email to The Free Press that the egg industry is currently operating at 25 million hens below what’s needed to keep up with demand. “Generally, we need about one bird per person to account for normal demand,” Moscogiuri said. “But we’ve seen the avian flu hit biannually since the spring of 2022.”

Hens lay about one egg per day 80 percent of the time, so to keep up with U.S. demand, the industry needs between 325 million and 330 million hens. If the bird flu disappeared altogether, rebuilding the egg industry to optimal levels would take about six to eight months. And nothing Vice President Harris mentioned in last night’s debate can change that fact.

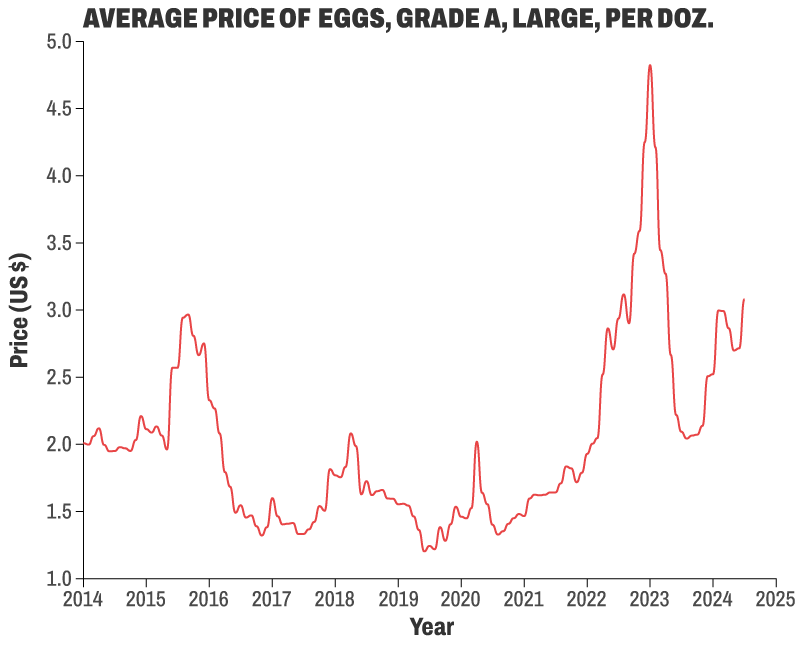

Meat: Meatpackers Make Money. Ranchers Don’t.

In August 2020, sirloin steak cost, on average, $8.88 per pound. In July of this year, prices hit a record high at $11.73 per pound.

According to the industry, several factors have contributed to this spike, including a drought in the Midwest and increased feed, labor, and transportation costs. But in 2022, when meat prices had risen to almost $10 a pound, the White House accused the industry of, well, price gouging. It noted that the four major meatpackers—Tyson Foods, JBS, Marfrig Global, and Seaboard Corp—had seen a gross profit increase of 120 percent.

Ranchers, on the other hand, didn’t necessarily see much of that money.

“Right now in the U.S., we have an inventory of cattle that is about the same size as it was in post–World War II America in the 1950s,” said Volpe—about 28.2 million beef cows. “It takes years for these animals to become market ready, so the prospects for the cattle inventory in the U.S. to expand significantly in the near term are very slim.” Which, in all likelihood, means higher prices still.

Reed Strate, 33, who runs his family farm in Kinsley, Kansas, where he raises beef cattle, says that increasing his herd would mean paying more for veterinary bills, among other things. Space is a constraint, too. “If I only have three fields I want to pasture, I’m limited on how many cows I can buy,” Strate said. “I can’t overgraze my fields.”

Despite the lack of inventory, it’s unlikely that Americans will change their meat-eating habits. “People want their steak, they want their bacon,” said Volpe. And that allows the big meatpackers to raise prices without much fear of falling sales.

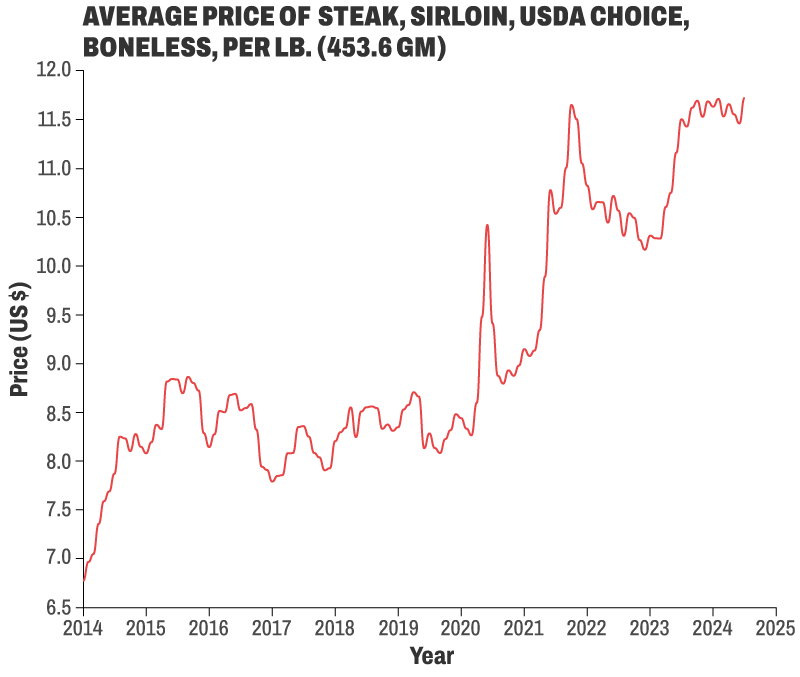

Salty Snacks Soar: Shrinkflation to the Rescue

Four years ago, a 16-ounce bag of potato chips cost about $5.00 on average. In October 2023, a bag of chips hit a high of $6.68 on average. Prices have since gone down to around $6.32 per bag, but there’s been some buzz about whether or not the huge conglomerates that control America’s snacks have, er, price-gouged by hiking their prices.

To be fair, the snack food industry has grappled with labor shortages, sugar, cocoa, and preservative shortages, and changing consumer behavior as more shoppers choose lower-priced private label brands over name brands. In a recent survey of 122 snack food industry executives, 82 percent said that increasing prices of raw materials affected their company, while 54 percent were concerned about consumers spending less on snacks.

Like most companies, PepsiCo and Mondelez, two behemoths in the snack food industry, raised prices on their products, passing inflation costs onto consumers—and then some. In both 2022 and 2023, PepsiCo’s net income was just around $9 billion—but get this: snacks, which make up just 27 percent of its revenue, contribute 44 percent of its earnings. In effect, the company is using its snack business to prop up its much larger drink business, which it can do because it is able to raise snack prices more or less at will.

For instance, during a 2022 call with investors, Hugh F. Johnston, Pepsi’s then-chief financial officer, was asked about the likelihood of snack food price increases. Here was his reply:

“Regarding pricing, we increased prices at the beginning of the fourth quarter based on what we knew at that point. And going forward, with the investments that we’ve made in brands, I still think we’re capable of taking whatever pricing we need.”

Translation: Our marketing is so good that people will buy our snacks no matter how much we charge.

Pepsi has also used another trick of the snack food trade to boost profits. It decreases the number of chips per bag for some products while keeping prices the same—a tactic economists call shrinkflation. This is not the sort of thing a presidential candidate is likely to rail about, but for consumers, it’s galling just the same.

Food shoppers are savvy. The Food Industry Association found that 63 percent of Americans now shop at a mix of grocery stores to keep their bills down, and there are more low-cost grocery options popping up throughout the country to accommodate this. German discount grocery chain Aldi, which already operates over 2,300 locations in the U.S., plans to add 800 more stores by 2028.

“In 2024 and 2025, food prices are becoming more affordable, [but] not because shelf prices are going down,” Ricky Volpe, the agribusiness economist, said. It’s because American consumers and businesses are adapting to the economic hand they’ve been dealt. Just like motorists will sometimes search for the gas station with the lowest gas prices, so do consumers sometimes seek out these lower-priced alternatives to help keep their food bill in check.

Will that economic truth matter when people go into the voting booth?